Count Dracula

Christopher Lee finally gets to speak Bram Stoker’s original dialogue as Count Dracula, but that may be the only compelling reason to watch Jess Franco’s 1970 adaptation. While the film’s opening title card promises to tell Stoker’s story “as written,” what follows is a curious hybrid: more faithful to the novel than the Universal or Hammer versions, yet ultimately less entertaining than either.

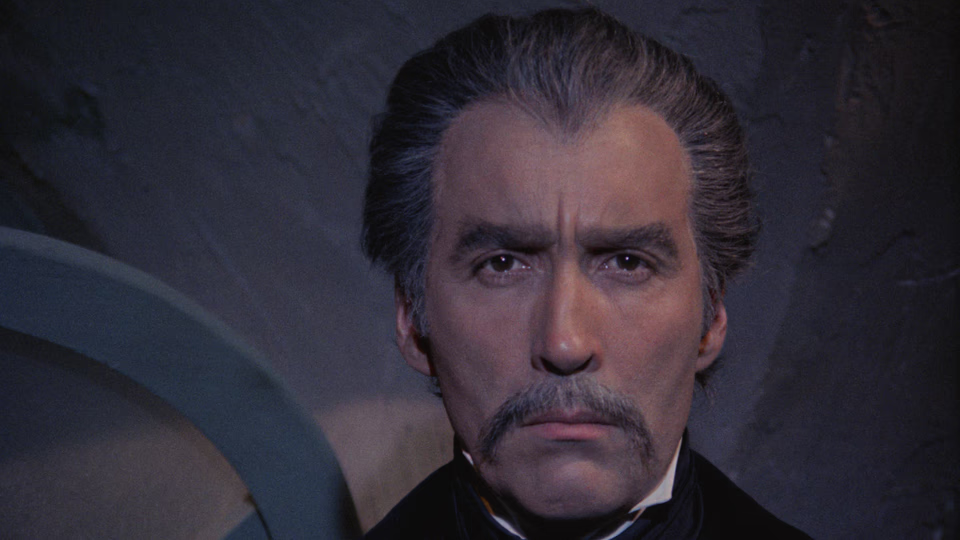

The film’s strongest segment arrives early, following Jonathan Harker’s fateful journey to Castle Dracula. Here, we find Lee, sporting the character’s literary white hair and mustache, clearly relishing the chance to finally deliver the Count’s most memorable lines including “The children of the night—what music they make.”

But this fidelity to the source material proves short-lived. Jonathan’s weeks of imprisonment in the castle compress into what feels like mere days before he makes an inexplicable leap from a window, only to wake up in London at a sanitarium run by Herbert Lom’s Van Helsing.1 The novel’s mounting dread gives way to rushed plotting, while the atmospheric arrival of Dracula’s ship—one of Gothic literature’s most memorable scenes—vanishes entirely, likely a casualty of the film’s meager budget.

Franco’s adaptation continues to make puzzling choices. Lucy, blonde in the novel (a detail that subtly explains Dracula’s attraction, given the rarity of fair hair in his homeland), becomes a brunette, while Mina is inexplicably blonde. Quincy Morris transforms from Stoker’s American cowboy into a British barrister, stripping the character of his distinctive frontier charm. These changes might be forgivable if they served some greater purpose, but they seem as arbitrary as the film’s pacing.

The middle act particularly suffers from crucial omissions. After Lucy’s staking, Dracula attacks Mina and then flees London without explanation. Gone is the novel’s tense cat-and-mouse game as Van Helsing’s team methodically tracks down and sanctifies Dracula’s various hiding places across London. The film replaces the novel’s memorable scene of Carfax Abbey teeming with rats with a bizarre sequence featuring jerking taxidermy animals, accompanied by a desperate musical score trying to manufacture terror where none exists.

Christopher Lee’s performance remains the production’s saving grace, though even this comes with caveats. Lee writes that the film “was made with the deepest of bows to the theater manager who invented the character,” and indeed, his Dracula feels more staged than lived-in, with line readings directed at the audience rather than his scene partners. Still, Lee regarded the film as “a good try,” but admits it was “a shadow of what might have been.”2

The film clocks in under 100 minutes, making it a modest time investment for Christopher Lee completists who simply must see every version of his Dracula. But even they should temper their expectations. What could have been a definitive, faithful adaptation of Stoker’s novel instead becomes a cautionary tale about the difference between reciting the words and capturing the spirit. Franco’s Count Dracula demonstrates that sometimes the least faithful adaptations can be the most truthful to their source’s essence.

Notes

-

This creates a gaping plot hole, as Harker knows Dracula is a monster who’s living next-door to the hospital. Once Van Helsing deduces the same, we get an awkward scene where Harker mumbles an unconvincing excuse about “not making the connection.” ↩︎

-

Christopher Lee, Tall Dark and Gruesome (Baltimore: Midnight Marquee Press, 2009), 288–89. ↩︎