Frankenhooker

Don’t let the title fool you. Director and co-writer Frank Henenlotter’s story of a man’s misguided attempt to reanimate his deceased fiancée by attaching her severed head to a sex worker’s body sports a surprising streak of feminist and trans-positive satire beneath its gory black comedy. Spoilers follow.

In a performance evoking Andrew McCarthy by way of New Jersey, James Lorinz, plays Jeffrey, a utility worker with a side interest in bioelectrical engineering. He opens the film at a party at his future in-laws. While his fiancée, Elizabeth, mingles with the guests outside, Jeffrey sits at the kitchen table fiddling with a brain attached to a makeshift electrical apparatus wired into a camcorder. Jeffrey has attached a lone eyeball to the brain’s center and can track its vision on a small television via camcorder.

Jeffrey’s imploring the eye to follow his hand. When it doesn’t respond, he plunges a scalpel into the brain, as if to depress a button. The act carries less a sense of malice than frustration at a failing experiment. To his delight, the scalpel seems to work, and the eye begins tracking his hand. Then Elizabeth’s mother interrupts, oblivious to the macabre experiment. and asks him to please pass the ketchup.

We follow Elizabeth’s mother outside, where she chides Elizabeth to “ease up on the pretzels.” Later, Elizabeth explains to a friend all the efforts she’s made to lose weight, saying: “Oh, heck. I’ve tried it all and nothing works. I’ve tried liquid diet, seafood diets, vegetable diets, fruit diets, pills, powders, Weight Watchers, and clinics. I even had Jeffrey staple my stomach and nothing helps.”

Elizabeth, played by Patty Mullen, proves attractive, despite the frumpy, floor length dress that conceals a figure bulging with odd curves like a perverse bodybuilder.

Later in the party, Elizabeth falls victim to a gruesome lawnmower accident, setting up the film as a collision course between Jeffrey’s interest in bioengineering and our societal insistence women adhere to unattainable physical standards.

After the opening credits, a distraught Jeffrey confesses his growing concerns over his mental health to his mother, saying “I feel like sometimes I’m plunging headfirst into some kind of black void of sheer utter madness.” Jeffrey’s mother responds with a blank face, asking, “Do you want a sandwich?”

Another memorable scene comes when Jeffrey brainstorms ways to acquire the body parts necessary to reconstruct Elizabeth. Frustrated by his lack of ideas, he produces a power-drill, identifies a segment of his brain, and drills. This produces a jolt of inspiration. Not satisfied, he drills again and arrives on the idea of preying on sex workers.

After identifying his victims, Jeffrey needs a way to murder them. On the television, a Morton Downey Jr.-like talk-show host disparages his guest, a sex worker promoting a program called “Hold On to Our Knowledge of Equal Rights”, or H.O.O.K.E.R.

“Don’t laugh, she’s right!”, says Jeffrey as the show shifts to guerilla-style footage capturing a muscle-bound pimp demanding money from a sex worker. The camera moves, revealing the worker as Elizabeth, prompting Jeffrey to shriek in horror at his hallucination. “All right, take it easy now,” he tells himself. “You gotta do the drill. You do the drill and you’re gonna feel much better now.”

A little self-trepanation later and Jeffrey’s rationalizing his plan to create a fatal form of super-crack. “I’m not shooting anyone,” he says. “I’m not stabbing anyone. I’m merely gonna place a lethal form of crack in their presence. They don’t have to take it. Nobody has a gun to their head. If they don’t wanna do it, they can… just say no.”

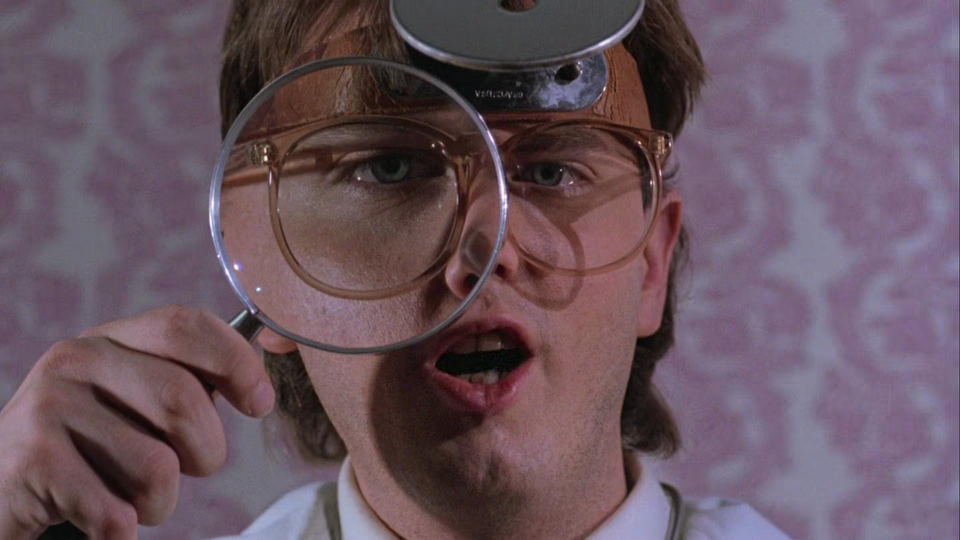

Soon, Jeffrey’s in a flop-house room with a bevy of sex workers. They think they’re indulging his fetish as Jeffrey, dressed in medical gear complete with a head mirror, inspects their bodies with a magnifying glass. The scene provides ample shots of naked breasts, legs, and buttocks, but Jeffrey’s excitement isn’t one of arousal but of engineering. He’s found the perfect set of parts. Now he just has to pick one girl.

And here shifts to full absurdity. When Jeffrey struggles to choose, the girls get angry and demand their money. Frustrated, Jeffrey tosses them the satchel with the cash, but inside the girls discover a gallon-sized bag full of giant crack rocks. They squeal with excitement. Jeffrey panics with horror.

The mood transforms to raucous party as the girls break out pipes and begin getting high. Jeffrey moves to intervene, but several of the half-naked girls straddle him, pinning him to the bed. “Oh, we need some music,” says another girl, popping in a cassette.

New Wave tunes fill the room. “Oh no, not the devil’s music. Turn it off!” wails Jeffrey.

The party morphs into an orgy as two girls strip and begin making out. Horrified, Jeffrey says, “Just stop that. Your body wasn’t meant to do that!”

Then the super-crack kicks in and the girls begin to explode. The effects are bloodless, akin to a robot exploding. At one point, Henenlotter proffers a point-of-view shot of a dismembered leg flying across the room.

The titular monster doesn’t appear until almost two-thirds into the movie. Patty Mullen’s performance proves memorable, with a convincing physicality to her jerking walk and spastic facial expressions. In an unexpected twist, she emerges not as Elizabeth, but as an amalgam of the deceased sex-workers. She flees Jeffrey and ambles back to their old New York City stomping grounds.

Here the film morphs into an absurdist female empowerment picture. In search of tricks, Mullen asks every passing man “Got any money?” When she encounters the usual demeaning brush-off, her preternatural strength sends men flying. And when she finds an eager client, consummating the transaction electrocutes him.

But Henenlotter saves his best twist for the finale, which sees Jeffrey’s head and mind grafted onto a sex worker’s body. Though some could read this as transphobic—exploiting a cisgender man’s horror of a woman’s body—I found it a subversive way to convey transgender struggles. If cisgender folks can react to the horror of Jeffrey forced to exist with a woman’s body, perhaps they can better understand how transgender folks might feel. Not bad for a movie called Frankenhooker.