Having a Wild Weekend

Director John Boorman’s feature debut sees Dave Clark and his band playing stuntmen working on a London-based ad-campaign. Clark and the spokesmodel, played by Barbara Ferris, ditch the production for a road trip to an island in South England with the ad company in close pursuit. Spoilers follow.

This film surprised me. The Dave Clark Five were an English rock and roll band with a string of Top 40 singles in the early Sixties. Given that, I went in expecting a knock-off of A Hard Day’s Night, and the opening did little to assuage my concerns. As the theme song plays, we watch the band wake up—they all share a bedroom, of course—and prepare for work. This musical sequence involves trampolines, rope climbing, messy meal preparation and other tropes designed to paint the group as kooky and fun.

But these gimmicks fade to the background as the film unfolds and Clark and Ferris begin their journey.

First, a bit about the campaign. It’s for the meat industry and Ferris’s picture looms all over London with the slogan: “Meat for go”. The commercial they’re shooting involves Ferris, Clark and the rest of the band sporting domino masks and black and white stripes and stealing slabs of beef from a London meat market. Yup, they’re meat burglars, predating the Hamburglar from McDonald’s by several years. The inspired absurdity made me chuckle.

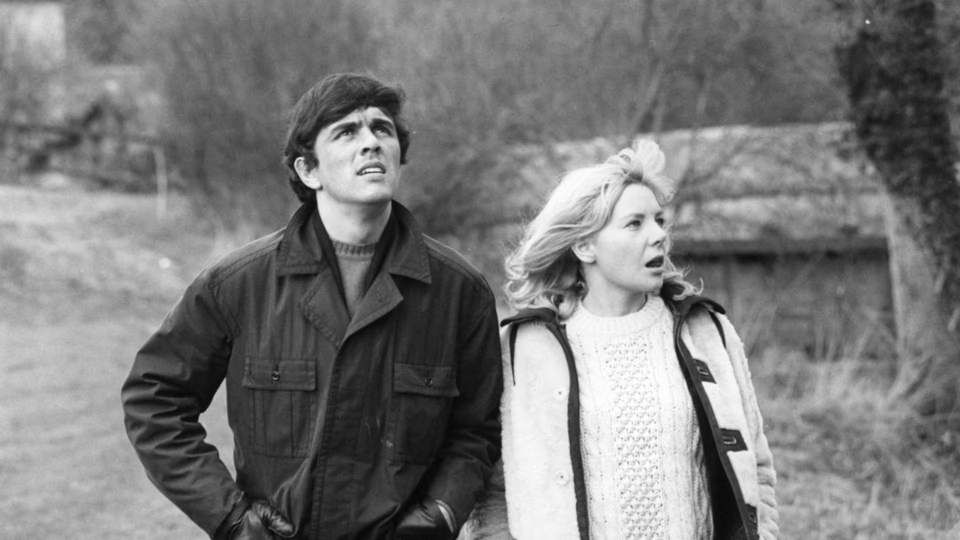

Back to Clark and Ferris. First, they tool around London in a stolen Jaguar. The high-contrast black and white photography stresses the city’s grime and intensity and feels like a precursor to famed photographer Anton Corbijn’s trademark style.

After touring London, the pair scuba dive in a rooftop pool. On the surface it proves just another goofy lark, but the contrast of Clark and Ferris in wetsuits swimming in near-freezing water under cloudy skies looks more like a desperate escapist fantasy than fun. It piqued my curiosity.

The pair then leave for the island. We learn Ferris dreams of purchasing it with her modeling money.

Their first pit-stop lands them in a desolate village. Overcast skies and leafless trees frame empty run-down houses. In one large building, they encounter a destitute group of beatniks.

This sequence provides the film’s first outright subversive note and hints we’re not in for a retread of A Hard Day’s Night. Disheveled and downtrodden, the beatniks stand in stark contrast to the romantic notion of a carefree nomadic lifestyle. Clark wants nothing to do with them, but they intrigue Ferris, who sits enraptured as the de facto leader espouses broken wisdom. Fed up, Clark goes for the car. Boorman underplays this scene to great effect, portraying the beatniks not as caricatures, but as believable vagabonds living a weary life.

Then the tanks arrive. The film shifts back into satire as the army rounds up the beatniks. Clark and Ferris escape and hitch a ride with Guy and Nan, a self-described “old married couple.”

They take Clark and Ferris to Bath. On the way, Clark and Ferris learn their adventure has become national news, with Clark accused of kidnapping Ferris. In Bath, the high contrast present in the London photography is gone, replaced with drab greys where the buildings blend into the overcast sky. A subtle comment on Guy and Nan’s numb existence.

At their home, Guy and Nan reveal their dysfunction. Nan vamps on Clark while Guy makes a clumsy pass at Ferris. Again, Boorman opts to underplay the scene. Rather than heighten Guy and Nan’s predatory behavior, Boorman only hints at the menace, affording both a sad undercurrent best illustrated by a sequence where Guy tries to woo Ferris by showing her his room of pop culture antiquities that paint him as a man clinging to a time long gone by.

Soon, the rest of the band arrives, and they join Guy and Nan in attending a masquerade party. The group has fun until police and press arrive, looking for Clark and Ferris, tipped off by the advertising agency that’s been trailing them.

A madcap chase ensues, with Clark and Ferris fleeing to the rural coast. There, they encounter a farm owner with plans to turn his property into an American Old West-style ranch. Again, Ferris seems enraptured, and again, Clark wants nothing to do with it.

She can’t understand his hurry to reach the island. “Why do you want to get there?” she asks. “Why can’t you enjoy the journey?”

“You give up too easily,” he replies.

With this exchange, the film clicked. Ferris and Clark are young lovers, and their encounters—the beatniks, the old married couple, the cheap entertainers—represent possible futures. Each stands within their grasp, and Ferris seems eager to settle, but Clark has his eye on something grander, a destiny of his own making.

With this in mind, the film’s recurring motif of cold, which begins with the breakfast scene’s frozen milk and is reiterated in almost every scene where we can see the performers’ breath, to the snow piles along the rural roads, along with the perpetual grey skies and bare trees, reinforces a sense of fatalism. Clark’s refusal to accept these destinies points to his resolve to escape this world, and we feel his quiet disappointment upon realizing Ferris can’t or won’t dream bigger.

The film builds to an unexpected downbeat ending that I won’t spoil, except to say that it cements the film as a rebuke to A Hard Day’s Night’s fanciful view of fame. The closing shot, from Clark’s POV, restores the high contrast of the earlier London scenes, but now he’s on the outside, fleeing the hungry mob who’ve already forgotten him.

What a discovery. I expected a goofy camp picture and came away impressed by the film’s existential undercurrent. Clark surprises with his confident screen presence and minimalist performance, and Boorman proffers terrific location photography and a measured tone that disguises a deeper film that has more in common with the British New Wave than a pop group vehicle. The soundtrack even proves incidental, with only four of the album’s twelve tracks appearing in the picture. The theme song, “Catch Us If You Can,” is catchy, if forgettable.

After watching the film, I began reading Boorman’s autobiography, Adventures of a Suburban Boy. He came up through television, directing stylish documentaries for BBC Bristol. One film covered an articulate beatnik teen, which inspired this film’s hippy encounter. Another production, shot in Glastonbury, uncovered its “Rabelaisian underbelly” which inspired this film’s Guy and Nan characters. The milk slogan came from an advertising campaign featuring a sprightly girl, Zoe Newton. “Drinka pinta milka day” became “Meat for Go.”

Interesting, but the behind-the-scenes drama proved more surprising.

When Boorman and screenwriter Peter Nichols first met Clark, they were “immediately depressed by his large, expressionless features and his flat, lugubrious voice.” What I saw as a confident, minimalist performance from Clark owed more to Boorman, who, having trouble getting Clark to perform, cut his dialogue to the bare minimum and had him play silent and taciturn. Boorman turned his attention to Ferris, which Clark resented. Ferris, in turn, was insecure about her appearance.

Tensions boiled over when Clark insulted the costume designer and received a sock in the jaw from her husband, one of Boorman’s few trusted confidants. Clark took three days to recover.

Nichols and Boorman wrote the script in three weeks. Four months from the day they sat down to write, the picture opened. Just before the film’s release, Boorman gave a press interview saying it was “not a great film.” Looking back in his autobiography, he maintains that position, saying “However brilliantly Peter and I had decorated the surfaces, it had a hollow center.”

Perhaps the troubled production colors Boorman’s perspective. Yes, it has a hollow center, but that’s the entire point. The celebrities, the beatniks, the libertines, the businessmen, they’re all hollow. In applying his documentary lens, Boorman has betrayed the truth behind the façade. For the film to proffer anything else would feel disingenuous.

Pauline Kael also saw something, as she praised it in The New Yorker, upping Boorman’s Hollywood credibility. Indeed, it may not be a great film, Mr. Boorman, but it is a good one.