Leatherface: Texas Chainsaw Massacre III

In many ways, Leatherface: Texas Chainsaw Massacre III delivers what folks wanted from the unexpectedly campy Texas Chainsaw Massacre 2: something visually and thematically similar to the original film. But the devil lies in the details. What made The Texas Chainsaw Massacre great was more than just grainy, saturated photography and nihilistic chainsaw horror.

This story sees a young couple and weekend survivalist waylaid by Leatherface and his monstrous family.

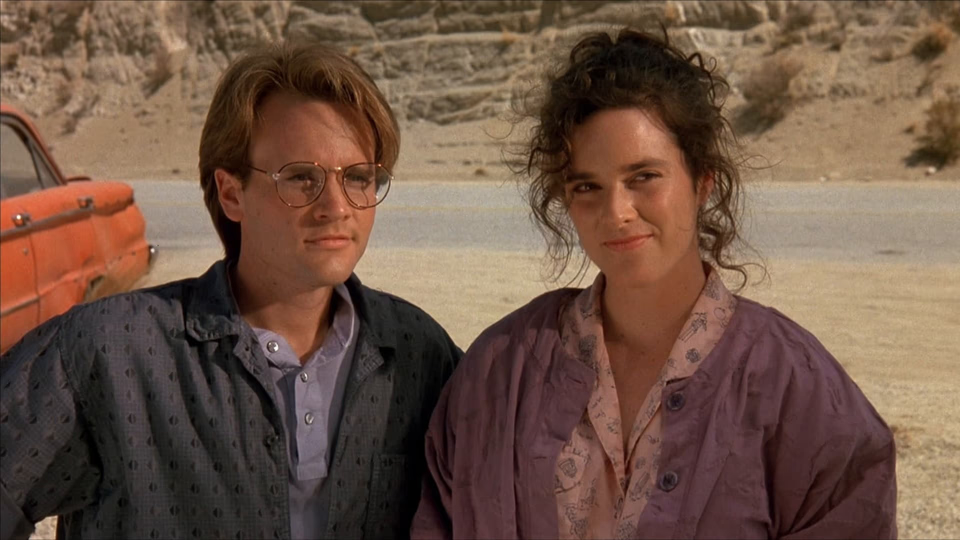

The couple, played by Kate Hodge and William Butler, open the film driving cross-country. First-time screenwriter David S. Schow, a horror novelist, makes the mistake of having them talk in exposition instead of as people. Both performers struggle with the clunky dialogue and the film seems doomed before it begins.

But then they stop at an isolated gas station and we meet the proprietor, played with smarmy menace by Tom Everett. His dialogue shines, leaving you wondering if it’s the script or the performers to blame for our grating protagonists. A young Viggo Mortensen appears as a handsome cowboy who helps them out of a jam. He attracts Hodge and thus threatens Butler.

Soon the couple is on the run, fleeing in their car. It’s dark. They can hear another vehicle but not see it. We see it’s behind them. Suddenly, the other vehicle turns on its lights, including a row of rooftop halogens, and roars its engine. “It’s coming from behind us!” screams Butler.

Honestly, by this point I was rooting for Leatherface and clan. Anything to silence this annoying pair.

Fortunately, the film introduces a third protagonist, a weekend survivalist played by Ken Foree. Best known for his leading turn in Dawn of the Dead, he’s easily the film’s highlight, injecting some much needed charisma and providing a character we invest in. He has agency, behaves sanely, and doesn’t verbalize every action.

The film settles into some nice cat-and-mouse in the dark woods. The actual night location photography shines.

Then Hodge finds Leatherface’s house, walks past a bunch of red-flag danger-danger warning signs like a wall full of CB radios, and follows a young preteen girl upstairs into a room littered with animal bones. The family member who catches Hodge from behind shakes his head and says, “They just get dumber and dumber, don’t they?”

This is Schow trying to have it both ways. Some lazy writing to get Hodge caught, followed by an audience-wink acknowledging it.

Next we meet Leatherface’s new family. Grandpa’s corpse still sits at the head of the table, but this family’s run by momma, a wheelchair bound woman speaking with a voice box. The preteen girl might be Leatherface’s kid—the script isn’t clear. Regardless, this change ruins one of the original film’s subtle horrors: that, left alone to their own devices, men would devolve into monsters. The patriarchy at its natural, horrific, conclusion.

The film stalls here. After binding and gagging Hodge like Marilyn Burns in the original film, they taunt and torture her—again like the original film. But where the original used this scene like a pressure cooker, ratcheting up the tension until Burns’ desperate escape, this film just fizzles, with all the characters inexplicably leaving Hodge alone before returning and resuming their torture.

Again, it’s Foree to the rescue with some much-needed action. Unfortunately, from here the film transforms from gritty horror into an action movie, as bullets start flying and Foree dispatches a family member in an elaborate manner, complete with a one-liner, all to a heavy metal soundtrack.

Then an inexplicable coda that pretends the film’s ending didn’t happen in order to facilitate a sequel. I challenge anyone not to gasp at the logic-defying inanity.

But, once you know the production backstory, it makes sense.

In the documentary, “The Saw is Family: Making Leatherface,” we learn from producer Robert Engelman that he’d commissioned the script from Schow, built sets, announced a release date, and even shot a trailer before hiring a director.

After getting turned down by the likes of Peter Jackson and Tom Savini, Engelman hired Jeff Burr, who’d just helmed Stepfather II: Make Room for Daddy. Burr, a fan of the original film, proposed shooting in Texas on 16mm film just like the original, but was blocked by Engelman who had already built the sets in California.

For the casting, Burr seems responsible for hiring Foree, while Engelman, seemingly oblivious to his own movie, says Hodge made a great scream queen because, “You don’t want someone to get on your nerves.”

Another red flag emerged when Engelman and Gunnar Hansen couldn’t agree on a deal and the role of Leatherface went to R.A. Mihailoff. While physically imposing, Mihailoff lacks Hansen’s manic intensity, rendering his Leatherface more sullen. As Burr says, he’s a teenager here instead of a child like the prior films.

These budgetary concerns bled into the production, with Engelman pushing Burr to move fast. Well into shooting, they were behind schedule and Engelman fired Burr, only to rehire him a few days later.

Adding insult to injury, many of the hardest scenes to shoot—the gory, practical-effects laden deaths—were later trimmed or excised entirely to appease the censors. Then, to top it all off, after positive test screenings, Engelman found studio money to shoot a new ending—without Burr—to tee up the expected sequel.

You see, Engelman and studio New Line weren’t looking to make a movie, but a franchise, one to replace the Nightmare on Elm Street series. Viewed in that light, it all makes sense.

Remember the trailer Engelman shot before he’d hired a director? It’s a tongue-in-cheek affair, with Leatherface looking out over a lake. As some serious-sounding voice over narration intones that “Legends live forever,” a Lady in the Lake style hand emerges from the water holding a cartoonishly large chainsaw. She lofts it into the air and Leatherface catches it, and a He-Man style bolt of lighting crackles out as man-and-machine are reunited before he turns and faces the camera, saw roaring.

It’s an amusing sequence, but an awful teaser for the movie. Consider: it alienated fans worried this new entry would hew more towards part two’s camp, while fans who went in expecting more of the trailer’s flippant humor would come away disappointed.

Is it any wonder the film opened out of the top ten, despite premiering on over a thousand screens?

You can’t manufacture a franchise. What producer would think they could with a novice screenwriter and hired-gun director? Well, now we know the answer.