Life with Father

William Powell plays the titular father, the patriarch of a four-son clan in 1883 Manhattan. The plot sees Powell beset by comedic familial drama, from the never-ending search for a maid, to his eldest son taking an interest in a pretty girl from out of town, and his wife, played by Irene Dunne, insisting he get baptized.

The production values shine. The saturated Technicolor pops the red in the casts’ dyed hair and the blue in Powell’s eyes, while the multi-room sets allow us to follow the performers across space, and the bustling exterior avenue, thronged with carriages and streetcars, lends a sense of turn-of-the-century New York’s urgent atmosphere. Indeed, Warner Bros. spared no expense bringing the popular stage play to the screen.

And yet, the film often betrays its stage origins. Aside from a church sequence and a scene teaming with costumed extras set in Manhattan’s famous Delmonico’s restaurant, the film confines itself to the Day house, a Manhattan brownstone. This proves disappointing given the exterior glimpses we’re afforded.

The performances all play to the recesses of a non-existent theater, vocalizing every thought and emotion. Powell and Dunne have proved themselves capable of more nuance so I can only assume their choices were intentional, meant to mirror the stage versions. To that end, they succeed, but I found the over emoting grating.

The film even retains the stage-style entrances for the performers, opening with a new maid carrying breakfast upstairs as the family comes downstairs, each of the three boys pausing on the steps in an awkward pose to say, “good morning” in a sequence reminiscent of a sitcom’s opening credits that would announce their entrance on stage. At the sight of each redhead, the maid licks her fingers and smacks her fist into her palm.

For his part, William Powell’s first color film sees him disappear into the role of Clarence Day. A sort of benevolent curmudgeon, Powell’ urbane wit and easy charisma vanish, replaced with Day’s egocentric blow-hard persona that booms, “Oh Gad!” at the slightest disturbance. While I appreciated Powell’s craft and apparent faithfulness to the stage role, I struggled with the Day character. Upon entering, he bellows and snorts about the maid’s service, oblivious to her presence, and drives her to tears with his callous behavior. In a recurring joke, an exasperated Powell says to Dunne, “What have I done now?”

Next, Dunne has to ask him for money to replace the coffee pot he broke in one of his outbursts. He balks, and she has to demure, almost begging him. While I appreciated Dunne’s deft navigation of the situation, the scene proffers nothing more than the already tired trope of women being flippant spenders and men allowing it despite knowing better. Disappointing.

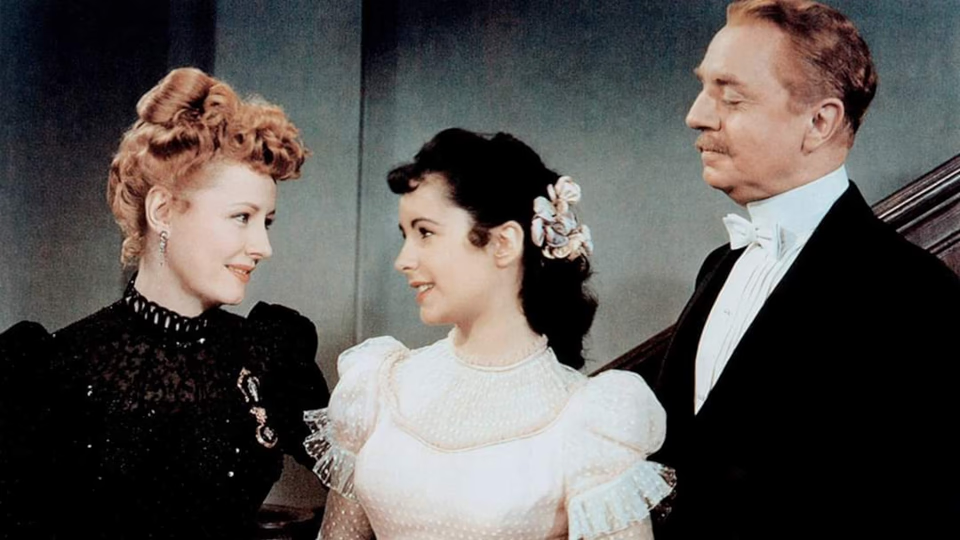

Soon Elizabeth Taylor arrives playing an out-of-town family friend. Like the rest of the young cast, she’s all wide-eyed over emoting, taking huge breaths between each line to project to a nonexistent audience. She and Powell’s eldest son hit it off, but complications arise when they realize she’s a Methodist and he’s an Episcopalian. Even worse, the eldest, clad in one of Powell’s old suits, finds he can’t make said suit do anything his father wouldn’t do. This leads to an idiot plot where he can’t explain this to Taylor, who herself proves oblivious to his inner conflict, and sits on his lap, to which he orders, “Get up! Get up! Get up!” which, in turn, sends her fleeing in tears. This entire plot thread felt so contrived and alien I couldn’t even appreciate it in a so-bad-it’s-good kind of way.

Anyway, the religious conflict reveals Powell’s character has never been baptized. This alarms Dunne, who fears for Powell’s soul. In another proffered comedic moment, she wonders if they’re even married, then looks at their kids and draws in a sharp breath and puts her hand to her mouth. Dunne resolves to see Powell baptized and sets about various machinations.

Meanwhile, the oldest son, determined to buy a new suit and not wear his father’s, partners with the next eldest son to sell quack medicine door-to-door. The pair decide to test the medicine on their mother first, as one ailment it purports to treat is “women’s complaints.” They almost kill her but demonstrate the mental acuity of toddlers by remaining oblivious that the elixir could be the poisoning culprit.

Compounding matters, the film runs almost two hours. Between this running time and the stage-ready performances, the film seems almost chained to the source material. Director Michael Curtiz stages some nice shots that showcase the film’s lush production, including a tracking show following Powell out of the house and across the street into a waiting street car. As the car pulls away, the camera tracks with it, then turns and follows a carriage carrying Taylor as it pulls up to the Day house.

But aside from this shot, Curtiz’s hands seem tied. The performances don’t offer any nuance requiring close-ups and the stage bound script relies on dialogue over action, leaving Curtiz with little to do. He tries having the characters move between rooms before settling into their dialogue while keeping as much of the lavish production in frame as possible. But a bit of dynamic camera work can’t rescue a comedy devoid of laughs.

I found the film insufferable, but your mileage may vary. If you enjoy 1950s sitcoms, you might enjoy Life with Father, as its episodic nature, overt moralizing and contrived plotting foreshadows them.