The Oblong Box

The Oblong Box suffers from an identity crisis.

Though the title card declares it “Edgar Allan Poe’s The Oblong Box,” it is not an adaptation of Poe’s short story.

I’m not holding this against the film. American International Pictures, which produced this film, was still milking their successful string of Poe adaptations starring Vincent Price and helmed by Roger Corman. The Poe short story, a minor work about a man who travels by sea from Charleston to New York City with his wife’s corpse, wouldn’t work as a feature.

Instead, the screenwriters craft an original story set in Victorian England, amalgamating several Poe themes.

The first theme, the brooding nobleman, comes via Vincent Price who plays Julian, who has returned from his African plantation with his brother Edward. An unseen calamity has befallen Edward, disfiguring him and shattering his mind.

Julian has locked Edward in an upstairs room, but with the help of family friend Trench, Edward plots his escape. Trench enlists a witch doctor to craft a pill for Edward to swallow that will make him appear dead.

The plan goes awry when Julian discovers Edward’s lifeless body first and immediately seals it in a coffin—the titular oblong box. Julian then reveals to Trench that tradition dictates that Edward must lie in state for the villagers to pay their respects. Unwilling to publicize Edward’s disfigurement, Julian blackmails Trench into providing a suitable body to stand in for Edward.

Trench acquires a corpse, but Edward is buried alive (another Poe theme). He’s unwittingly rescued by a group of grave robbers who deliver the coffin to a local doctor, Neuhartt, played by Christopher Lee in a ridiculous wig that could be described as an “aging Beatle”.

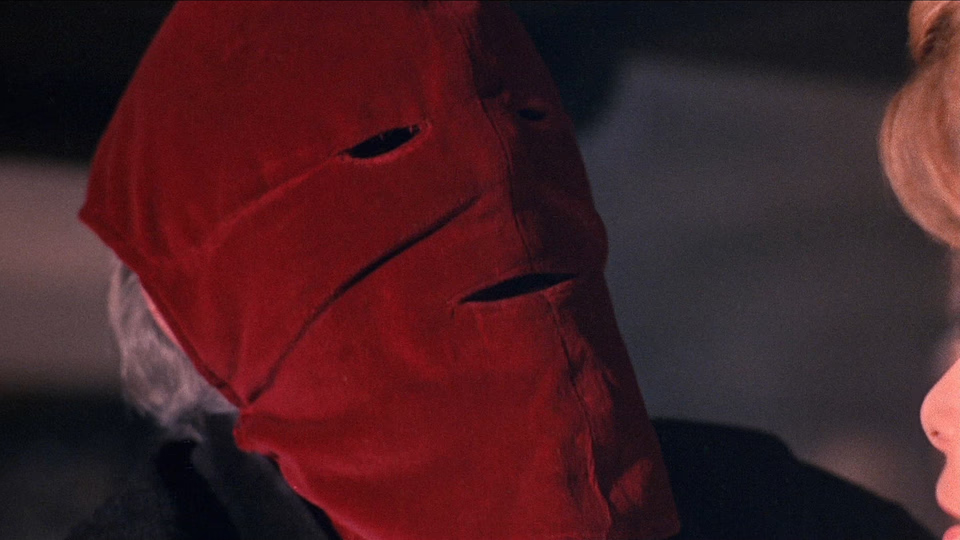

After prying open the coffin, Neuhartt discovers his new corpse isn’t a corpse at all. Edward then blackmails Neuhartt into providing him with food and shelter. The script reaches for another Poe theme—masked figures—as Edward dons a crimson highwayman’s mask and sets out on a path of bloody revenge leading back to Julian.

In cramming in all these Poe themes, the film forgets to include any audience surrogates. Nearly every character proves corrupt, quick to blackmail or commit other atrocities. This cripples any emotional stakes and even weakens the narrative ones, as we’re hard-pressed to care what happens to these characters. It’s gothic horror minus the archetypes.

Director Gordon Hessler struggles with the dichotomy.

Consider the opening sequence, an African voodoo ritual. Hessler shoots the scene primarily from the victim’s point of view, through a slightly fish-eye lens. The result looks not unlike a music video, with the shaman mugging for the camera.

Credit to Hessler for innovating, but the formal rigor feels at odds with the material. Perhaps Hessler sought to differentiate these early African scenes? A valid choice, but the visual disconnect makes the subsequent shift to Victorian England feel like we’re cutting to a different movie.

All that said, there’s a moment when Hessler’s more contemporary style and the script’s cynical characterization click.

Edward’s first target is one of Trench’s accomplices, who’s set to flee England. Edward poses as a coach driver. The accomplice boards and directs the driver to take him to Dover. Edward drives off. The dark night and rhythmic clatter lull the accomplice to sleep. He’s awakened by the coach stopping. Confused, he realizes they’re not in Dover. They’ve stopped on a deserted country road. Edward hauls the accomplice out of the coach and interrogates him for the witch doctor’s location. When the accomplice can’t provide it, Edward slashes his throat.

And here, everything gels. As Edward continues stabbing the accomplice, Hessler shoots from the victim’s point of view, showing the masked Edward, silhouetted by the night’s sky, driving his knife down into his victim’s chest before spurring the coach on and walking into the fog-shrouded woods.

Slasher iconography at its finest.

Had the film embraced this angle, and framed Edward as an unstoppable masked killing machine, it might be regarded as an important step in the slasher evolution—a bridge between Psycho and Halloween. But alas, instead it pivots to a Phantom of the Opera-style tragedy, with a subsequent brothel scene painting Edward as clumsy and frightened.

The film can’t decide if it’s meant to be a gothic horror, tragic melodrama, or contemporary graphic thriller. Though the film cribs from Poe’s themes, it lacks the strong narrative and engaging characters necessary to drive them. At best, the result is uneven. Fans of Vincent Price and Christopher Lee should find it passable, as the pair give their usual professional best, but it’s not enough to salvage the mismatched material.