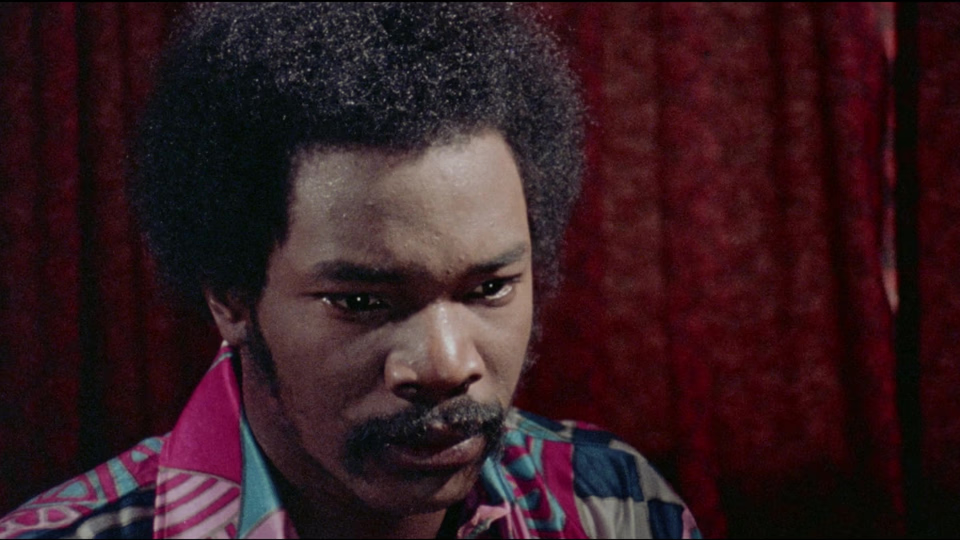

Welcome Home Brother Charles

Charles, a young black man, finds himself convicted and imprisoned following an arrest on trumped-up charges in which a corrupt cop attempts to castrate him. Upon his release three years later, he returns to his impoverished neighborhood, conflicted between his thirst for vengeance and desire to go straight. Spoilers follow.

If possible, go in cold. The less you know, the better. Even alluding that a plot twist exists somewhat spoils it. I’ll start with some non-plot related context in case you’re on the fence.

Director Jamaa Fanaka shot this feature while an undergraduate at UCLA, filming on weekends over seventeen months. His formal craftsmanship impresses. The south central location photography lends a gritty verisimilitude. The shift from color to black and white photography for the prison sequence amplifies the environs’ dull monotony, as do the interstitial stills, which convey time’s passage while masking budgetary constraints. Then, the handheld-POV shots during Charles’s walk through the neighborhood after leaving prison exude a sense of urgent discovery.

But now we must talk about the plot. Again, if you haven’t seen the film, go watch it.

Still here? Okay. For its first two acts, the film operates as a meditation on the plight of Los Angeles’s inner cities, and how internal and external forces combine to oppress the black residents.

Charles opens the film as a pimp and drug dealer. He’s harsh with his girls and thinks little about dealing drugs in his community. He’s also carrying on an affair with a cop’s wife. When said cop finds out, he goes ballistic and attempts to castrate Charles. At his trial, Charles recognizes the judge as a frequent trick. After exiting prison, Charles learns his partner abandoned him, taking over his operations and even stealing his girl.

It’s a messy situation. No innocents, just varying degrees of corruption. Charles recognizes the cycle of crime and prison and vows to escape it, but he also struggles with his girl dancing topless at his former partner’s bar.

Carmen, a prostitute who falls for Charles, offers a way out. The two try straight life. She gets a job as a waitress, but he struggles to find work because of his prison record. Frustrated, and still holding a dim torch for his former girl, one night Charles spies the cop who mutilated him on television.

From here, the film takes a hard turn and morphs into an exploitation story where Charles uses his prehensile penis to take vengeance on the white men behind his arrest and incarceration.

Yes, you read that right. First, he visits the white men’s wives and uses his penis to hypnotize them. Later that night, he appears outside their houses like Dracula, willing the wives to let him indoors. Once inside, he makes his way to their bedrooms, where his penis chokes the life out of their husbands.

Charles makes his way through the racist cop and prosecutor before the police catch up and corner him on a rooftop. With Charles threatening to jump, the cops find Carmen and urge her to talk Charles down. Instead, she screams for him to jump and the film ends.

A fascinating watch. Fanaka’s documentary-like focus on the depressed community in the first two acts delivers such an immersive experience that the third act pivot into exploitation horror shocks.

Drawing such a clear delineation between realism and fantasy prevents the exploitative elements from diminishing the first two acts’ authenticity. It also provides a novel way for Fanaka to confront fears of interracial sex and stereotypes of black male sexuality. By depicting these fears heightened to ludicrous levels, he points out their inherent inanity.

Granted, the over-the-top nature pushes it beyond horror and into satire, but Fanaka’s take isn’t far removed from Bram Stoker using Dracula as an allegory for transgressive sexuality and Jewish immigration fears. Except Fanaka empathizes with his monster and uses the first two acts to—if not justify—at least contextualize his actions.

All that said, the film’s biggest weakness is its ending, or lack thereof. None of the plot threads resolve, the film just ends. I can appreciate Fanaka’s nihilistic message, but also can’t help feeling like he ran out of ideas, money, or time. Or maybe a good movie just leaves you wanting more.